SLAC’s upgraded X-ray laser shows its soft side

This leap in capability will allow scientists to investigate quantum and chemical systems more directly than ever before.

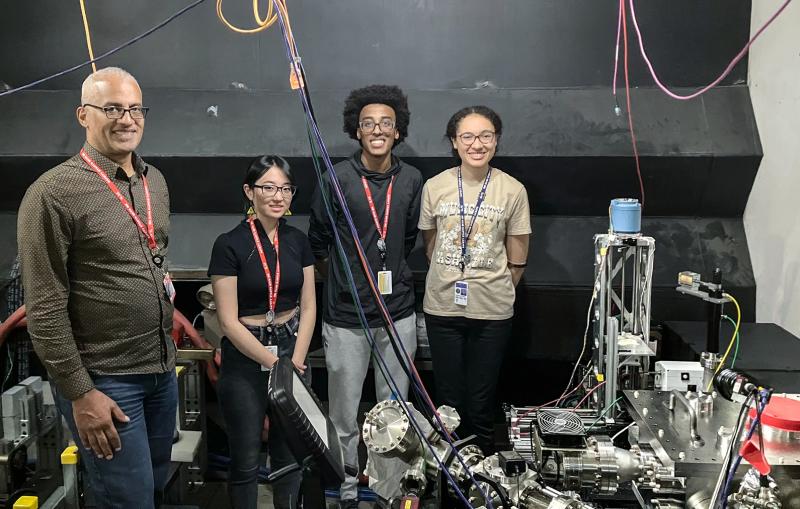

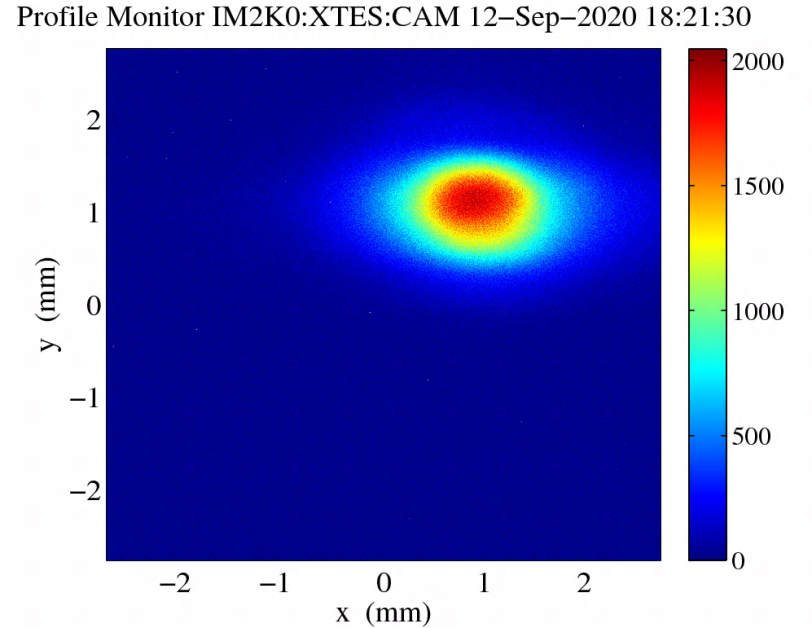

The second phase of a major upgrade project is now online at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), the pioneering X-ray free-electron laser at Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. On September 12, scientists ushered an electron beam through a new undulator to produce “soft” X-rays. This follows the upgraded facility’s first light in July, produced with another undulator that generates “hard” X-rays.

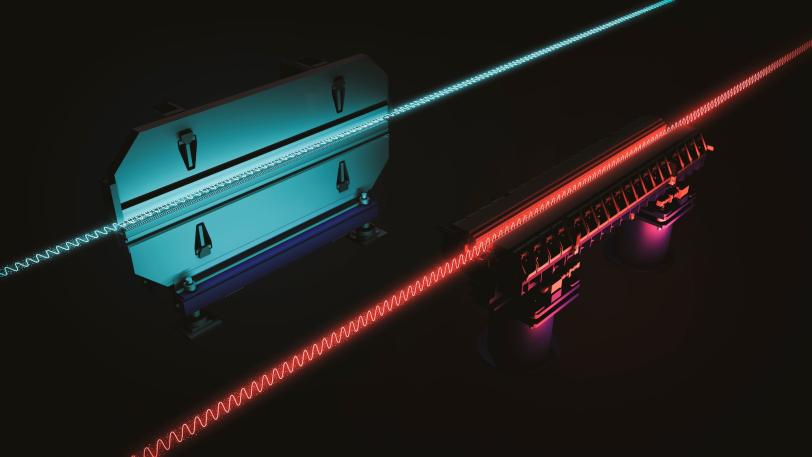

Undulators, integral to X-ray free electron lasers like LCLS, use an intricately tuned series of magnets to convert electron energy into intense bursts of X-rays. Hard X-rays, which are more energetic, allow researchers to image materials and biological systems at the atomic level. Soft X-rays can capture how energy flows between atoms and molecules, tracking chemistry in action and offering insights into new energy technologies.

The new soft X-ray undulator, the second major piece of the LCLS-II upgrade project to fall into place, was designed and built by DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and installed at SLAC over the past 18 months. While LCLS isn’t the first facility to house more than one undulator, it will be the only one capable of shining both beams on the same sample simultaneously, expanding the scientific reach of the X-ray laser.

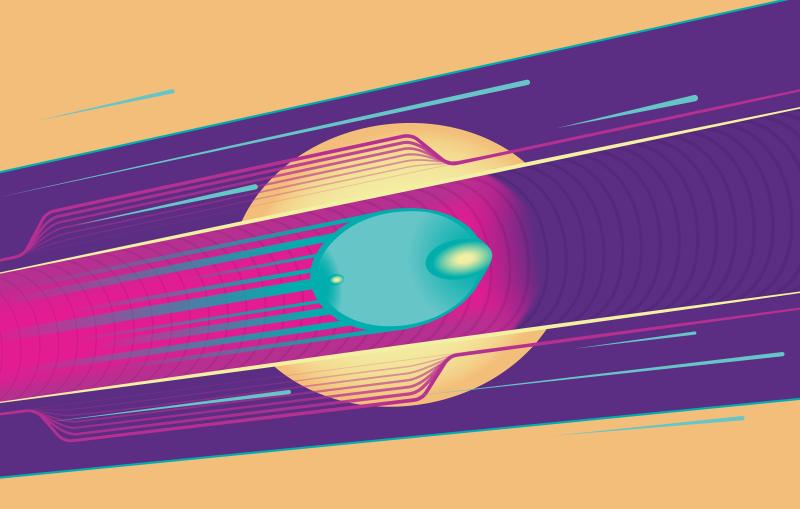

The soft X-ray undulator will produce X-ray pulses that last for less than a millionth of a billionth of a second, allowing scientists to investigate quantum and chemical systems more directly than ever before. These ultrashort pulses will soon be put to work at the new Time-resolved atomic, Molecular and Optical Science (TMO) instrument, the first of the LCLS-II era. There, it will allow scientists to investigate – at the quantum level – fundamental phenomena central to complex processes such as photosynthesis, quantum computing, and the forming and breaking of bonds that govern all chemical reactions.

When LCLS-II is completed in the next two years, it will increase the X-ray laser’s average power by thousands of times, producing up to a million pulses per second compared to 120 per second today. The final step is currently being installed: a brand new accelerator that uses cryogenic superconducting technology to ramp up to these never-before-achieved repetition rates.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.